Is Oxfam Avoiding Tax? (revised)

Controversies about corporate ‘tax dodging’ tend to follow a common pattern. Critics expose the web of complex structures and opaque transactions used by a company and point to the advantageous tax result. It might be legal, they say, but it smells fishy.But one person’s egregious exploitation of loopholes, can be another’s innocuous interpretation of the rules. The people responsible for the company’s tax affairs tend to feel that they are being stung by an unfair and unwarranted attack based on misunderstanding and innuendo. They issue a terse statement along the lines of ‘we pay the right amount of tax according to the law’, and hope it all blows over.

The #taxmantra – @soongjohnston

But after the noise has died down we are left no clearer about what where the boundaries of responsible tax planning versus unacceptable avoidance might be.

This week, unusually, the NGO doing the criticizing was the free market Institute for Economic Affairs, and the Finance Director emerging blinking into the sunlight of unexpected public scrutiny was Oxfam’s Alison Hopkinson.

Richard Teather at the IEA called into question Oxfam’s use of tax planning via its trading arm Oxfam Activities Ltd and the way it uses the government’s gift aid scheme. “It is a strange philosophy that condemns actions in others whilst busily engaging in them oneself.”

Alison Hopkinson at Oxfam responded that “The IEA blog is a classic case of smoke and mirrors using partial information to make a case against Oxfam where none exists. The fact is that we are very careful to comply not just with the letter of the law on tax but also the intention behind it.“

You can simply pick sides based on where your sympathies lie (NB: my allegiances: I am both a shopper and donator at my local Oxfam store. I support Oxfam’s mission, but I wish they would get more serious in their tax advocacy).

However, I think the case raises interesting points which could push us to try to clarify thinking about the blurry zone between uncontroversial ‘good’ tax planning and bad/aggressive/immoral stuff, and the extent to which there could be more well-defined criteria for making the distinction (or can at least having a sensible discussion about it).

Tag my Bag

The bit of Oxfam’s tax planning that is most interesting is the ‘tag my bag’ scheme which allows it to convert sales of donated goods (which are explicitly excluded from gift aid) into apparent cash donations (which are therefore eligible for gift aid), simply by getting people to sign a form and tick a box before they drop of their pre-loved items.

This scheme was first developed by Sue Ryder stores in 2006, and has been adopted by Oxfam and many other big charity shops. Legally the way it works is not exactly as explained in the blurb above. The small print says that rather than donating items when you drop them off instead you appointing the charity as your agent to sell them, and that then you have the choice to donate whatever they make, minus the agent’s commission, back to the charity (which the government will then view as a cash donation and top up by 25%). Higher rate taxpayers they can also claim back an additional amount themselves.

Similarly when you buy something at a charity shop that has a gift aid sticker on it, you are not really buying it from the charity at all, but from an anonymous seller, who will then in all likelihood donate the cash that they have (in theory) earned back to the charity.

Of course, most people don’t read the small print and the cycling of cash to the seller and back to the charity only happens in theory, so the transaction in practice feels exactly like you are donating to or buying from the charity shop in the normal way. If ‘round-tripping’ donations via some obscure paperwork to turn an old pair of shoes into a cash donation sounds complex, convoluted and artificial it is. But is it tax avoidance?

Is this tax avoidance?

There have been various arguments either way, and I collect them here:

The case that ‘tag your bag’ is tax avoidance

- It achieves a result that parliament did not intend: Section 416 of the Income Taxes Act makes one of the conditions to claim Gift Aid that “the gift takes the form of a payment of a sum of money.“ Parliament has clearly excluded donations of goods from the Gift Aid scheme (IEA).

- It is an artificial structure set up purely in order to gain a tax advantage (IEA)

- The legal structure does not accurately reflect the commercial activity. Does the ‘donor’ really think that they are keeping ownership of the goods until they are sold, and then making a separate donation? (IEA)

- It is based on manipulated intra-group pricing to maximise the tax benefit. Is 3% a realistic arms-length commission for selling goods through a staffed high street shop? (IEA)

- It is heavily marketed: Donors can claim Nectar points on goods but only if done so through the “Tag your Bag” scheme (IEA)

The case that ‘tag your bag is not tax avoidance

- It achieves a result that parliament intended: “Let’s not forget the purpose behind gift aid – to allow people to reallocate some of their own tax to causes they care about” (Oxfam)

- It is specifically approved by HMRC guidance “These arrangements are agreed, sanctioned and promoted by HM Revenue & Customs. The tax guidance for charities contains sections explaining how to do it.” (Charity Tax Group & Oxfam)

- The activity is not carried out in secret. “The information in the blog is published in our annual accounts – tax dodgers tend to be rather more secretive.” (Oxfam)

There is an interesting discussion at Richard Murphy’s blog. about whether the fact that the government knowingly permits the practice and HMRC issues guidance on it means that it must be OK. Andrew Jackson argues that this confuses the role of executive and legislature, and in any case would also rule in much of the behaviour by big companies that Oxfam decries as ‘tax dodging’.

So at the core of the argument seems to be the disagreement between point 1 for and against. Are the results that the structure achieves in-line with what parliament intended or not?

The law on gift aid is clear that it applies to donations which “take the form of a payment of a sum of money. Oxfam say that all they are doing is acting like a charitable branch of Ebay or Cash Converters making it easy for people to convert their unwanted stuff into money which they then donate to the charity.

I’m not a tax lawyer or an accountant (obviously!) and I know that there are various learned folks with different views on the matter (please do pop in with comments). But I thought it might be interesting to look at the numbers in more detail.

What do the numbers tell us?

Say I have a DVD of the latest James Bond blockbuster Spectre that I don’t want anymore – I could take it to my local Oxfam store and donate it appoint them as my agent to sell it for me, or I could take it to another place a few doors down (CEX is currently paying £2 for a copy of Spectre and selling it for £5) and collect the cash myself and then donate that to Oxfam. How would the two compare in terms of gift aid treatment?

If I took the DVD to CEX I would be get £2 which I could donate to Oxfam and the government would kick in an additional 50p of public money.

If instead I take it to the Oxfam store and they sell it for £5 on my behalf, this would be accounted for under the scheme as 15p commission for the Oxfam store and £4.75 for me which I then donate to Oxfam, with the government adding £1.19.

If the purpose of the Gift Aid incentive is to encourage people to donate money to charity and isn’t about the selling of second hand goods, it seems odd that the incentive should be so different depending on which outlet is doing the business of selling second-hand stuff.

You can see how it works for Oxfam Activities Ltd. (i.e. the trading arm) by looking at their accounts.

[UPDATE: Reading over the accounts I realise have got the original interpretation wrong – to avoid confusion I have edited this section. I have moved the previous bit to here – Maya]

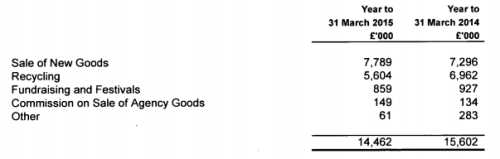

Oxfam’s trading income is spread across the charity, and Oxfam Activities Limited. Overall Oxfam and Oxfam Activities have a turnover of £75 million from donated goods, and makes a net trading income of £20 million (or around 25%). Oxfam activities limited turnover includes s £149,000 ‘commission on the sale of agency goods’ (i.e. ‘tag my bag’).

Based on a 3% commission including VAT this means that this is associated with £5.96 million of additional sales of donated ‘gift aided’ items, which are then remitted (minus the commission) directly to Oxfam as cash donations on their behalf (presumably showing up under ‘regular donations’) and attracting a further £1.45 million of Gift Aid.

Tag your bag sales are therefore worth around 6% of the donated goods trade (less than I had previously thought).

What remains true is that 3% does not seem to be a commercial commission rate, since on average around 75% of overall turnover for donated goods is used to cover the costs of the donated goods business.

It looks to me like HMRC have been too lenient in their guidance and enforcement of the scheme in allowing charities to charge such low commission rates, which bump up the apparent cash value of bags full of assorted second hand donations beyond their true worth.

I am not sure what the ‘correct’ commission rate should be, but if we take the average profitability of the business as a guide to work out the net value of goods donations then 75% of takings are needed to cover the cost of the business, giving a 25% return to the seller who can then donate this to Oxfam . In this case the amount of gift aid from the government might realistically be £372,000, or about a quarter of what they get under the more generous interpretation.

In the grand scheme of things the cost to the public purse is pretty small (I could say the difference between the Gift Aid that Oxfam gets from the scheme vs the more realistic number is the equivalent of 35 nurses, but that would be silly), but it makes for an interesting in exercise in sheding light on the broader questions in the debate on tax and corporate responsibility:

- What is meant by ‘tax avoidance’? Are practices being questioned from an ethical standpoint or is a case being made that the company is abusing the current rules ?

- What criteria are being used to make that judgement? Can they be reliably and consistently be applied to Oxfam, Paladin in Malawi , SABMiller etc…

I think that for the debate to advance beyond the current stage of noisy argument there is a need for stakeholders and experts from different camps to get deeper into the detail of these discussions together, beyond the headlines. Campaigners, tax practitioners, tax academics, economist and development experts are increasingly (but still too rarely) coming together to build understanding. Perhaps tax professionals within the finance department of charities themselves should also contribute to this dialogue.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 8 Comments

Maya is asking the questions that really have no easy answer. As everyone in the tax world will admit the only way we can know if tax is being avoided is via the Courts considering the application of the statute to a set of facts. Or, as Ribeiro PJ said in Collector of Stamp Revenue v Arrowtown Assets Ltd [2003] HKCFA 46, para 35:

“[T]he driving principle in the Ramsay line of cases continues to involve a general rule of statutory construction and an unblinkered approach to the analysis of the facts. The ultimate question is whether the relevant statutory provisions, construed purposively, were intended to apply to the transaction, viewed realistically.”

Ultimately, it is not really definitive to note what the IEA thinks, or Oxfam, or any other commentator, because they are only expressing an opinion. Their opinions may or may not be persuasive but they remain opinions. The same is true of my opinion. But I think it clear that some hallmarks of avoidance are present in the Tag A Bag scheme. To start with, the legislation is explicit on the conditions of Gift Aid. Oxfam’s website deals with this in the following way:

“Can you reclaim gift aid on goods I donate to an Oxfam shop?

Yes we can. Our great new Tag your Bag scheme means that every time we sell something belonging to you, we can raise 25% more from the government through Gift Aid – at no cost to you.”

Viewed realistically, do we think donors go to their charity shop with the intention of appointing them as agent to handle the sale of their surplus DVD? (Alternatively, would we think it likely they would sell via Gumtree and then donate the money to a charity?) Are shoppers warned they are buying from an individual? If there is a refund does it go back to the “donor?

Another hallmark is whether there are steps in the transactions that have no commercial purpose (not no commercial effect). I cannot see the commercial purpose here but I can see the “fiscal alchemy” of turning the base metal of a donated good into the gold of a cash donation. If construed purposively does it seem like an arrangement aimed at sidestepping the restrictions on Gift Aid?

Many commentators have said this is not avoidance because there is a clear policy intention to benefit Charities, or that HMRC has given its blessing through guidance, etc. In terms of avoidance I don’t think these are any help. The Patent Box is clearly policy but many would argue it institutionalises avoidance. HMRC’s views, or guidance, are clearly important in whether or not they will challenge a transaction or series of transactions. But if we use that as a proxy for avoidance/non-avoidance then it would also apply to other disputed cases, like Amazon or Google. (And who knows, maybe HMRC is investigating Oxfam in the way it was investigating Google but not admitting it publicly?)

If the policy arguments are correct then it would seem so much more straightforward if the law was changed. There is precedent for this in the area of charities. For many years there was a policy of allowing charities and some charitable trusts to claim tax repayments “in-year”, and not (other than Gift Aid relief) as legally required, as part of their annual return. To rectify the position Finance Bill 2012 made it possible for such in-year repayments to be claimed on or after 6 April 2012.

(https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/192102/repayments_charities.pdf)

If all this is a storm in a teacup then maybe the Charities should be asking for the law to be changed to align it with practice (as with in-year repayments), It would remove uncertainty and presumably simplify life for donors, Charities, and their shops.

Thanks Iain,

Yes I agree it is a bit of a storm-in-a-teacup – but I think it is interesting because it demonstrates so clearly why the ‘you-are-tax-dodging/no-we-are-just-using-the-rules’ conversation keeps going round in circles i.e. there is no easy answer and the assumed clear dividing line between fair/unfair behaviour disappears when you look closely at any one case . So either opposing sides just dig in and shout louder, or stop shouting and try to work out if there are any common principles of responsibility which apply equally to the cases of Oxfam and to companies that have been in the spotlight, or as you say accept that the only real arbiter can be the courts.

Oxfam’s statement is awful (what were they thinking?) and you do wonder what Oxfam’s campaigning team would have said had an MNE undertaken similar structuring. That said, I don’t think Oxfam’s campaigning has ever actually criticised a scheme that is conceptually like this, and therefore the accusation of hypocrisy remains unproven (for me).

Is it tax avoidance? What are the consequences if it is? What are the consequences if it is not? Are you, or have you ever been, a tax avoider? I can’t remember sometimes why we argue about it. The debate has largely become meaningless, although admittedly a huge amount of fun.

Is it legally effective? I think I would have been prepared to give an opinion that it was. And still would be.

Ultimately, this appears to me to be a case of a charity which, understandably, wants to increase the money it has available to use on good causes. Gift Aid provides for relief on donations of cash, but not for donations of goods, although these goods have a cash value. There are good reasons for the legislation not providing for Gift Aid relief on donations of goods. So Oxfam, in common with other charities, puts in place a very slightly artificial scheme to improve its financial position substantially. Theres no real mischief here. I can donate a cardigan and they can sell it, or I can get them to sell it on my behalf and donate the proceeds to them (even if I don’t really think about it in that way). One is better for them (and for me) than the other. Let’s do that one. Duh.

Different structures give rise to different tax results. Sometimes you put in place a slightly different structure to that which you would have chosen without professional advice. I don’t think, and have never said, that the tax debate is purely about “what’s legal” but we are not yet in a position where we cannot look at tax legislation and be at least a little bit creative in improving our position, or the position of our client.

I’m just leaving this quote here. It’s not a favoured quote by any in the tax profession. But it seems to me to reflect the public position taken by NGOs like Oxfam in relation to tax.

“Always one must go back to the discernible intent of the taxing Act. I suspect that advisers of those bent on tax avoidance, which in the end tends to involve an attempt to cast on other taxpayers more than their fair share of sustaining the national tax base, do not always pay sufficient heed to the theme in the speeches in Furniss, especially those of Lords Scarman, Roskill and Bridge of Harwich, to the effect that the journey’s end may not yet have been found.”

If you think Lord Steyn was correct in McGuickian, I don’t see how you can defend tag-a-bag. The definition of unacceptable tax avoidance is constantly developing, but the tag-a-bag scheme seems to me to fall squarely within the Ramsay jurisprudence, as it stood in 1997.

“It was thought that if the steps were genuine, i.e. not sham or simulated documents or arrangements, the court was not entitled to go behind the form of the individual transactions. In combination those two features–literal interpretation of tax statutes and the formalistic insistence on examining steps in a composite scheme separately–allowed tax avoidance schemes to flourish to the detriment of the general body of taxpayers. The result was that the court appeared to be relegated to the role of a spectator concentrating on the individual moves in a highly skilled game: the court was mesmerised by the moves in the game and paid no regard to the strategy of the participants or the end result. The courts became habituated to this narrow view of their role.

On both fronts the intellectual breakthrough came in 1981 in Ramsay, and notably in Lord Wilberforce’s seminal speech which carried the agreement of Lord Russell of Killowen, Lord Roskill and Lord Bridge of Harwich. Lord Wilberforce restated the principle of statutory construction that a subject is only to be taxed upon clear words at [1982] A.C. 300, 323C-D. To the question “what are clear words?” he gave the answer that the court is not confined to a literal interpretation. He added “There may, indeed should, be considered the context and scheme of the relevant Act as a whole, and its purpose may, indeed should, be regarded.” This sentence was critical. It marked the rejection by the House of pure literalism in the interpretation of tax statutes. “

Still happy to give that positive opinion. Unrelated parties (transfer pricing irrelevant, inter alia), altruistic motive of donor/seller, strong arguments for Parliament not drafting for Gift Aid on donations but not objecting to principle of allowing charities to find a way to do so, HMRC endorsement of scheme.

That said, implementation still a little suspect in cases. Charity I signed up to today (i) were reluctant to let me take a photo of the GIft Aid form; (ii) told me I couldn’t claim the Gift Aid relief as a higher-rate taxpayer; (iii) said I was getting Gift Aid relief on the donation rather than on the cash proceeds, even when I queried it; and (iv) said I couldn’t keep the proceeds less 1.5% rather than donate them. It’s usually the implementation…

It’s almost ALWAYS the implementation….

‘We are not yet in a position where we cannot look at tax legislation’ – I agree and we should not aim to get into a position where the legislation is irrelevant . Destroying the rule of law will not help anyone. As Maya says, these issues are not as straightforward as some campaigners like to suggest and, whilst the legal/ illegal debate has been oversimplified, ignoring the law is not an answer. So I am fully behind Oxfam using the law to raise maximum funds for what it considers to be good causes, but it should not blame companies for using legal incentives , given by governments, to do what the company boards think is valuable- eg making profits to re-invest , pay to shareholders so they re-invest, pay employees and creditors, keep prices competitive etc. Let’s apply the same logic to all.

There’s a useful blog by Stephen Daly on legitimate expectation and how it might or might not apply to Oxfam. It includes an interesting link to a Court case in 2010 when Oxfam lost when trying a similar sort of argument.