This is what development looks like

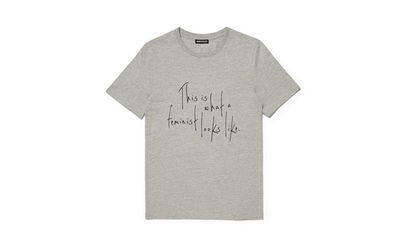

This week the Daily Mail created a stir by reporting that t-shirts produced for the Fawcett Society by Whistles, and modelled by British political leaders, had been made in ‘Sweatshop conditions’ in Mauritius.

I’m not a big fan of gesture politics, overpriced boxy t-shirts, or the Daily Mail. But I am a feminist and I know a little bit about the apparel industry.

This is not what a sweatshop looks like.

This looks like a well equipped, purpose built factory. The workflow is organised, the garments are not piled on the floor and the lighting is good. Compagnie Mauricienne de Textile (CMT) is a major supplier for clothing brands such as Topshop, Burton and Next and, The Fawcett Society say they were assured it had a host of certifications for ethical production standards.

CMT is clearly no fly-by-night back-alley operation. As the NGO Labor Behind the Label has said the conditions are industry standard. I’d go further and say it looks like one of the world’s better apparel factories. Nevertheless Whistles and the Fawcett Society have been condemned for sourcing t-shirts here, and everyone involved is scrabbling to distance themselves. As a spokesman for the Lib Dem leader said ‘Nick Clegg had no idea where these T-shirts were being made and can only assume that the Fawcett Society were unaware of the origins, or they would not have asked him to wear it.’

Of course it is not possible to judge a factory’s labour standards by looking at a few photographs on the internet. It could be that fire doors are bolted shut, that the management are abusive, that two sets of books are kept to disguise unpaid overtime or that trade unions are suppressed – all of these things are all too common in the industry, but it is not what the Daily Mail found here (that would have taken them more than a casual afternoon’s tour with the Managing Director to uncover).

The Mail say this lady is a migrant worker called Primerose Marcelin. Erm…..I think she may be a Mauritian supervisor, but great investigative reporting.

What they do report is that migrant workers are paid 62 pence an hour, that they live in dormitories that are basic by Western standards, that they work 45 hours a week, with additional overtime, and that they have enough money to send some home. If all of this is true, then this is not a sweatshop, but a factory that appears to be in compliance with Mauritian law and with international standards like the Ethical Trading Initiative base code.

Low wages and communal dorms may be an unpalatable contrast to the t-shirt’s empowerment message, inflated pricetag, and celebrity endorsement, but the reality is that work on this unglamorous side of the fashion industry has been a way out of poverty for many millions of women and men, and a first rung towards industrial development for many countries. As Naila Kabeer, Professor of Gender and Economics at LSE, among others, has argued, the garment industry, for all its problems has enabled poor rural women to have more choices and power over their lives than before.

This then, is what development looks like.

It is not an argument for sweatshops, or against trade unions. But it is an argument that companies that comply with laws and industry standards, and work to address risks and problems should not be condemned just because they employ poor women in developing countries.

One thing that is true is that migrant workers are particularly vulnerable to abuse, discrimination and exploitation. Agents sometimes give predeparture loans to pay for airfares at extortionate rates of interest, leading to situations of debt bondage. Accommodation provided can be squalid. If this is happening at CMT then Whistles and other buyers certainly have a responsibility to know and to work to resolve the problem. The article notes that there were reports back in 2007 of placement agents lying about wage levels to attract people to pay inflated placement fees. But The Mail does not follow up to see what has happened since.

In 2010 and 2011 the Institute for Human Rights and Business held a series of meetings in the London, Mauritius and Dhaka on human rights risks for migrant workers, including one where CMT shared their experience and the policies they had put in place to prevent this happening and to protect migrant workers. I don’t know if these measures are working or not, but I think the views that it is simply ‘more ethical’ to not buy from any developing country supplier is misguided.

(This also highlights a key dilemma in trying to implement higher ‘living wage’ commitments, which is that if jobs pay over the market rate they will be rationed in some other way, and jobseekers will be willing to pay up-front fees to gatekeepers to get these jobs. This can exacerbate the very risk of bonded labour situations highlighted above).

One question I have not seen raised in any of the coverage of the Fawcett Society controversy is what is the driver for people to migrate for garment factory jobs in the first place.The attraction for workers is perhaps clear. The article says that wages in the Mauritian factory are £120 ($190) a month. The minimum wage in the garment industry in Bangladesh where many migrants come from has recently risen to $68, and in practice wages are often lower.

Still, though,this does not explain why companies are willing to pay higher wages for the same workers to make clothes for the same customers in Mauritius than they would if they were in Bangladesh. Why doesn’t the company simply shift production to Bangladesh where labour costs are lower? (and if they did, would this be a good thing or a bad thing?)

Mike Flanaghan of Clothesource (who knows a lot more about the apparel industry than I do) has a compelling explanation. Chances are if you buy a £45 t-shirt you won’t find a ‘made in Bangladesh’ label in it. Bangladesh’s garment manufacturers are predominantly domestically owned and are trapped at the precarious low cost end of the apparel trade by unreliable power supplies, port delays, politically motivated labour disputes and their own low-investment business model. There are too many undercapitalised factories. They compete on price rather than on service or quality and as a result cut corners on safety and are not able to invest to outcompete inefficient competitors or develop higher margin production. Low wages reflect low productivity.

Workers command higher wages if they migrate to Mauritius, not because they have more skills, or more rights, nor because the factory owners or the consumers are more moral but because the infrastructure problems are fewer and the factories are better equipped and managed. Production in Mauritius is not a tale of ‘the race to the bottom’ but of industrial upgrading. A key barrier to this happening in Bangladesh is that foreign investors like CMT are largely kept out by restrictions which enable the politically powerful members of the domestic Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association to maintain a closed shop.

The corporate responsibility movement is no panacea for pervasive injustice, but sometimes it can bring competitive and reputational pressure to bear on the powerful in a way that creates change in a system. Its key tools are standards (such as for working out what is a sweatshop, and what is just industrialisation in a poor country), strategy (for working out where the most powerful accountabilities are that might drive change) and well placed moral outrage. The Daily Mail is just pretending to take this stuff seriously, lets not play along with them.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 3 Comments

Two great books on this topic are the travels of a T-shirt in the global economy by pietra rivoli, which really goes into this question in detail. And farm girls, I forget the author, which interviews workers in garment factories to find out what they think. Its better than working on the farm.

I also saw a paper that showed expansion of garment industry leads to women obtaini g more educ and having more control over family planning so maybe this is what faminism looks like.

One thing though, did I read that these workers are being paid substantially below prevailing wages in Mauritius? That’s unusual afaik wages in factories in poor countries are usually high relative to local alernatives. Wonder what explains that.

Hi Luis,

Sorry I managed to leave this comment stuck in moderation for ages…… (and then I wonder why I don’t get many comments!). Thanks for the book recommendations. Another good book is Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China by Leslie Chang.

The reports I saw were that wages were above the minimum wage, but below the called for increased minimum wage (and way below the calucated living wage), but significantly higher than prevailing apparel sector wages in Bangladesh, where many of the migrant workers come from.

I think the role of migrant labour answers your question about wage rates compared to local alternatives.

But the question that rarely seems to get asked in these debates is what stops CMT and other international manufacturers opening more factories and improving conditions and productivity in Bangladesh itself – i.e. the role of domestic governance and infrastructure barriers, and of restrictions against foreign investors which Mike Flannagan highlights.